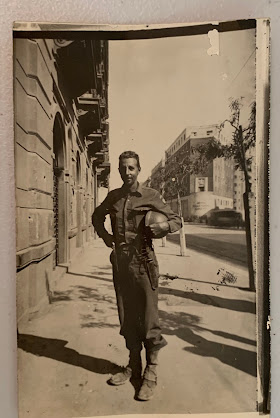

Christmas 1941 continued (Chapter 20 of A Shower of Frogs)

December 7, 1941, had wrenched us from our peaceful pursuits. Discharge day would send us back to peace. Between these dates was a host of experiences as numerous as the cosmos and as varied as snowflakes. If we were to pick out one vexation in prison that crowned all other vexations it was the sense of wasted life. In normal military life this sense was staggering; in prison, it was an insidious and corrupting force. It gnawed away at the nerves of us all, both old and young. It gave us a sharp sense of the irreplaceable quality of lost time. Waiting. Waiting, Waiting. Men chose the Munich detail to avoid thinking about it, only to sit in a boxcar for five hours-waiting.

Food was certainly our immediate practical concern. It was also easier to talk about. While our tongues told of the hunger, our eyes reported the waste. Few of us could articulate the waste; all could speak of food. In early November and December, until it grew cold, I spent hours walking in the yard adjacent to the barracks.

I was sometimes joined in my deliberate pacing by Coppola, Stubbs, or someone else. Usually I paced by myself. At the time I felt I could never again visit a zoo. That feeling passed. I neglected to count the steps it took to encompass the yard, but as I remember it, it was about half the size of a football field. I walked around counterclockwise (being a suppressed left-hander). I would alter this by pacing back and forth on the longest side.

I walked beside one of two eight-foot barbed-wire fences that were separated by a long zigzag trench, six feet deep, with sides supported by logs. At the corners of the yard were guard towers built of logs rising to a height of twenty feet and manned by one or two German soldiers with a machine gun. Across from the long side of the yard, fifty yards distant, was a British camp where vigorous soccer games never ceased to amaze us Americans. How did they

have the strength for such frivolous exercise? At one end of the yard, I could stand and look a mile away into a forest. Late in autumn some of the trees turned color and were reminiscent of Tom Wolfe's description of America in old October. It was a neat twist of irony that I should be in Wolfe's beloved Bavaria, but not as a tourist, while at the same time remembering his impressions of the Nazis in Germany, while all this was mixed up with thoughts of America at Halloween. Looking out beyond the fences to the far distant fields, I remembered the corn stalks and pumpkins on the plains of Illinois, which led me to recall a line from Robert Sherwood's Abe Lincoln in Illinois: "And this too shall pass away" I was comforted and sustained by this thought during the winter of our incarceration.

Except for news brought in by recently captured prisoners and from unreliable information drifting around camp, I lost contact with the world. The silence within the glider when free of prop wash was symbolic of the silence that surrounded me. I was cut off not only from the men I had known for nearly three years, from my friends at home and in England, but also from the life of the world.

The Germans gave us blank forms for written messages. Never believing they'd really be delivered, I nevertheless sent a number of them. I knew that for some period of time my correspondents would be unaware of my whereabouts. The silence that surrounded me went out from me. There was nothing I could do about it unless the letters got through to them. (Many did.) This worried many of us, and as Christmas and New Year's approached our apprehension increased.

***

We all sat about, in the closing days of December, just before Christmas, wondering and speculating on whether we'd get one Red Cross box apiece for Christmas, as had been rumored. We listened for the sound of the truck that brought the boxes. We'd heard the truck, run to the window or door of the barracks to check. It was usually the garbage or coal truck. We kept looking, kept hoping, as we approached Christmas Eve.

182